Falls sections are timeless. When a group of skaters are sitting around a TV laughing hysterically at someone taking a horrible fall, it is because we feel their pain. Falling unites us all. We have all found ourselves on the ground, clutching our shin, knee, or ankle in the fetal position “doing the Peter Griffin.”

Brooke Howard Smith once said, “Rolling will give you two things in life, bad knees and good friends. Make the best of both.” If someone asked me to sum up rollerblading in one sentence, that would probably be the one.

“Given the choice between the experience of pain and nothing, I would choose pain.” — William Faulkner

People still get flexed today, but old school falls sections are amazing. Years of experience and improvements in skates have made it easier to do everything from skating around, to grinding, and landing. The extra confidence gained from wearing pads often led to people getting crucified. Watching a lot of these clips, it often seems like the skater didn’t completely take into account all of the surroundings and ways he could get hurt.

A few months ago a friend of mine broke his elbow skating a mini ramp. This was far from his first trip to the emergency room over the years. As he was leaving the hospital, he looked over the simple instructions from his doctor on his discharge papers: Keep arm in sling. Take vicodin for pain. STOP ROLLERBLADING.

“It was fun though. Pain don’t hurt man, I don’t care about pain. I mean, I’m a skater, you know?” — “Smart move” Rob

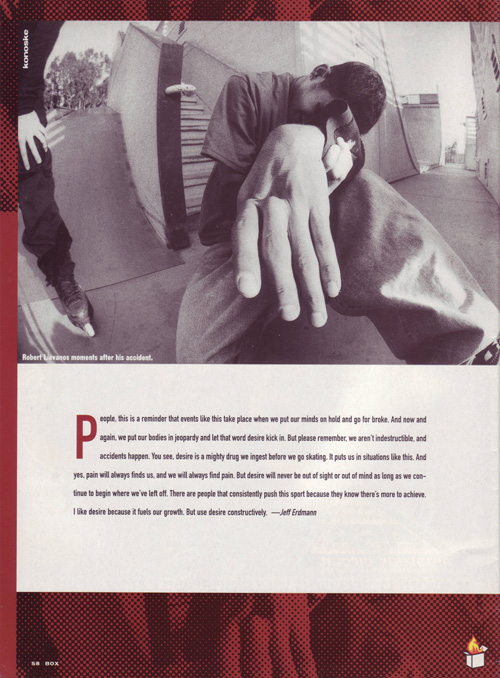

It is hard to explain to people that don’t skate why we have such devotion to something that causes us so much pain. Even if people don’t admit it, there is something about the pain in skating that we embrace. It is a part of what we do. In the 50% section in “Espionage,” Dave Temple took the worst part of skating, the rawest and ugliest part, and turned it into something beautiful. I think this section helps illustrate the elation felt after lacing a trick. The possibility of falling and getting hurt makes the feeling of landing something even better. The lows make the highs even higher. Ryan Jacklone’s mother once observed of her son’s skating that it was like he got to leave the Earth for a moment. The feeling of rising above the ordinary is part of why we take the pain that comes with skating.

Every day I am reminded of what rollerblading has done to me. Every time I look in the mirror I see the surgery scar down my stomach from the time I ripped my right kidney open, and almost in half, at the age of 15. Starting to the left of my belly button, it goes in a small hook around it and lengthwise up my stomach stopping a few inches below my chest. In the middle of my stomach on the left side sits a small scar where a feeding tube once went directly into my stomach.

I remember being in the hospital with a tube going through my nose and down my throat, a feeding tube going directly into my stomach, a catheter, and a morpheine drip, reading the newest issue of Daily Bread with Dustin Latimer doing a 360 soul on the cover, and my friend Jon bringing me a copy of “VG10” the week it came out. My parents, the doctors, and nurses were all horrified when one of my first questions to them after my surgery was “When can I skate again?”

Reading Michael Braud’s blog entry about finding out that he has Polycystic Kidney Disease took me back to the moment when I arrived at the hospital and pissed straight red blood for the first time. My body had gone into shock a few hours earlier, and this was the first moment that it became clear to me that something was seriously wrong.

It was surreal to find myself in a hospital in Marrakesh, Morocco last summer yet again on the verge of death with IV’s and monitors hooked to my body. While filming a documentary in the High Atlas Mountains, our crew was trapped for two days in the remote village of Aguerzane. Soon after our arrival the region was hit with its first rainfall in over three months. We watched in awe as the rain caused massive mudslides down the side of the mountain, washing out the roads we took into the mountains and destroying the people’s crops. We had no choice but to wait out the storm.

On the hike out of the mountains I began to become incredibly sick from eating chicken soup cooked by one of the villagers. It felt like Wolverine from the X-Men was trying to claw his way out of my stomach. I kept hoping the pain would subside, but after three days I relented and went to the hospital.

My friends had seen a young woman die after driving her scooter into the side of a truck the day we got back to Marrakesh. An ambulance arrived about 45 minutes later and the EMTs threw her into the back of the ambulance like a piece of meat. Hearing this story didn’t exactly build my confidence in the Moroccan health care system.

Doctors stood around me, one running her hand up my scar while conversing in Arabic with the other. I felt that their conversation was along the lines of “Well, he is already cut here, maybe we can go in from the side.” Nurses and doctors asked me in Arabic and French to describe my symptoms with hand motions while I repeatedly screamed “ENGLISH! ENGLISH!” at the top of my lungs, scared that they were going to cut me open.

In moments like these you can pinpoint what you value in life, and it makes you question everything you think you believe about the world around you. It made me think of something Lisa Simpson once said, “Prayer, the last refuge of a fool.”

Michael Braud July 20 at 11:43 pm

When you start talking about extreme sports with someone who doesn’t know much about them, the question of broken bones and serious injuries is soon to come up. In my case of having a decent number of broken bones and concussions, the next question is always, “And you still rollerblade?!” These questions show the outsiders’ perspective on physical pain and a seemingly intrinsic human characteristic of staying far away from pain at all costs. The extreme sports enthusiast’s response that not only are they still a part of something that has put them through a large amount of pain, but that they love it and do it at almost every possible chance they get, shows that our minds deal with pain in a much different way than the average human being.

If you plan on being in an extreme sport as a career, you should plan on falling… a lot. If you are learning a new trick or pushing something you’ve learned to the next level, or, hell, if you’re doing a trick you’ve done a thousand times, there is room for error and that error usually lands you flat on your ass. Sometimes there’s a nine foot drop before your ass hits something, sometimes that thing is a rail, sometimes it’s stairs, and sometimes, instead of your ass, you land on your head. If you ever think to yourself, “Why did this happen to me?” as I often have, it’s because, dumbass, you decided it was a good idea to jump off of a roof, or grind down a large rail with flat and slanted segments, try to jump over one of said flat segments, or tried to toe roll on a curb to make your friends laugh, or simply because God hates you personally. If you’ve pissed God off in some way, that’s on you, but all of these other scenarios are good ways to get yourself hurt. They’re also good ways to feel like a fucking badass if it all works out, and that’s what keeps us going back every single day. So when you fall, understand that it’s going to happen and it happens to everyone (even Haffey and Aragon… yeah, I know, I didn’t believe it either, but it’s true.) Take it like a professional, get over it, and learn from it.

If you’re scared to fall, get out of action sports, you’re making us look like pussies. If you’ve just started, you won’t bust your ass in public like it’s your job forever. However, it will happen on occasion and, if you’re doing things right, those occasions will be seriously unfortunate accidents probably involving someone with a PhD. Other than that, there will be tweaked ankles, bruises and scars to show off to your friends, light head trauma, and something to be a part of that will shape you into a fucking amazing human being if you push yourself that far through the pain. So, I say, “Pain, fuck you, I hate you, you’re no fun, and you ruin my party, but, without the knowledge of you, death defying stunts and life in general wouldn’t be such a rush, so I understand why you‘re here.”

At the beginning of his section in the England team video Volume, Dustin Latimer said… “I like to skate mainly because I love to skate, and it’s fun and it’s challenging. It’s just kind of a way just to push myself, you know. Say I were playing soccer, it’s a way you want to better yourself. Skating is just a way for me to do that.”

The chant heard several times throughout the Hoax II of “Make it perfect, make it perfect” while not repeated verbatim, or even thought of consciously is a guiding principle of all who skate. We are all trying to reach that perfect moment where the mind and body focus to overcome our doubts and fear to achieve what we didn’t know was possible, but it doesn’t always work out that way. One of the greatest things skating can teach is humility. If you begin to feel arrogant, the taste of the concrete will son you quick.

“We cannot learn without pain.” — Aristotle

unnescessarie shows his broken hands…i really don´t like to see this kinda things

“patinem pra sempre”

later.